| Mon

Tue

Wed

Thu

Fri

Subscribe

| |||

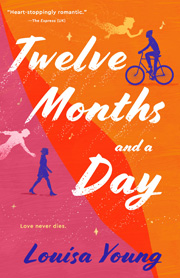

Dear Reader, I'm feeling particularly fine today. I stopped for a minute, took a personal inventory and I realized I've achieved some major accomplishments lately–projects that I'd been working on for over a year. Not bragging--I just decided today that I don't ever take the time to stop and celebrate my personal achievements, and I should--because once the moment is gone, it's gone. Instead of celebrating when I accomplish a personal goal, I toss it aside as ‘no big deal’ and immediately I start making plans to move on to the next project. But it is a big deal! And today's the day I'm going to pat myself on the back. I always take the time to chastise myself when I screw up, but why is it so difficult to be my own cheerleader when I succeed? Maybe it's those self-defeating thoughts that try to creep in and ruin the party: "Better not feel too good Suzanne or something bad will happen to put you in your place." I don't even know where I picked up that dialogue, but I'm not buying it anymore. "You did good today, Suzanne. I'm proud of you. Today's your day to celebrate!" Thanks for reading with me. It's so good to read with friends. uzanne Beecher P. S. This week we're giving away 10 copies of the book Twelve Months and an Day by Louisa Young. Click here to enter for your chance to win.

| |||

Twelve Months and a Day: A Novel | |||

Outside, time had continued to pass, the bastard, and it was becoming spring. The sky seemed higher, and tiny pale green tufts had appeared on the larches. Pistachio tinged with rose. 'Like a poem', he thought. But not a lyric. He wasn't going to be writing a song about pistachios and roses. He took out a song he'd been writing before he'd ended up in hospital: "Sorrow Follows," about lying beside your beloved, about sickness and deathbeds. He'd knock that one into shape for her. Sorrow follows everywhere you go. 'This is what I remember', she'd said. But he felt riddled with strange happiness. 'Sorrow may follow me,' 'but I won't invite it in.' He'd get the Vincent out soon, now it was a little warmer. Noth- ing like a motorbike on a cold sunny morning. He wasn't short of time, after all. Best to do things. He cleared a space on the kitchen table, and set out a knife and fork, salt and pepper. He fried two eggs and ate them, with toast and shito sauce. Kwame had brought up some of Auntie Dolores's when he came to the funeral. "You'll be needing that," he'd said. He ate his eggs. 'That's for you, my love. No more falling behind with the eating.' He wrapped his hand round his second cup of tea and took it to his desk. Glanced to Jay's laptop, sitting there, pretty dusty now . . . he opened it but—nope, not today. No point looking at her messages. It would only be eternal spam. Charities. A message about a pair of leggings some algorithm was convinced she wanted. 'One day when we're all dead the algorithms will still be spamming away, sending their junk out eternally across the universe, trying to flog each other control leggings and online guitar courses . . .' The cat twined round his legs as he logged in on his own machine, to find emails from the bank and the lawyer. He replied blindly: 'whatever you think best'. One from PRS: royalty payments from songs from long ago, keeping the ship afloat. A handful from girls with Russian names wanting to make him happy. And one from George, lead singer of the Capos. 3 Are Ghosts Allowed? FEBRUARY IT WAS JUST an ICU, and Nico had seen them before. A chair drawn up behind a blue curtain; wires connecting from the instruments, an empty mug on the stand. And a body, laid out, unplugged. A dead body. He'd seen those before, too. It was him. 'But I'm here . . .' He stepped forward. He was dead all right. 'Whoa.' 'I was in the pub'— 'Where's Róisín?' He'd been at the pub having breakfast and everyone had suddenly gone crazy running around. Róisín at the heart of it, staring. She'd been holding him. 'Then what?' 'I died?' 'Jeez, is that what I was doing?' She wasn't there now. He couldn't remember what had happened! 'Christ, all that fuss and' 'then you don't remember.' 'Fuck!' Nico was a logical man, trained, professional. 'I'm having an' 'electrochemical brain incident', he thought. 'I'm undergoing a near-death experience—fugue—' 'But that body is dead. Unresponsive, no chest movement . . . not long dead, not yet cold, with that waxy, pulled-in look . . .' He put his hand to his wrist, thinking to take his own pulse. It settled like snow: hardly touching, feeling nothing. Neither of him was breathing. 'Okay then, yeah, that's it. I just need to slip back in now. That's what they say, isn't it? Float around the ceiling, see everyone crying, someone calls you toward the light, you say no thanks, mate, not yet, check if some researcher's hidden something on top of a cupboard, and then you slip back into your body.' He sat down suddenly on the plastic chair by his mortal remains. He found himself smiling at the body. At himself. "All right," he murmured. He'd seen it happen—the sudden ragged swoosh of an independent breath, the relief and the laughter, when you thought you'd lost someone. 'But how do you do it? You kind of . . . swoop?' How often had he been on the other side of this, talking people back into their bodies, hold on now, come on, don't leave us . . . breathing his breath into their lungs, CPR, defibrillators and AEDs, stand back! Restarting their hearts. Nobody was doing this for him. He didn't seem to be swooping or slipping. He lay down, gingerly, alongside himself, and put his mind to it. 'It's psychological.' 'Oddly hard to focus when you can't breathe.' Róisín'd told him years ago about an Irish thing: if a person dies without the last rites, you must kiss them to take in their last breath, then when the priest arrives you give it back to them in another kiss, so he can absolve them of their sins while there's breath in them. 'No breath here.' Nothing. He wondered if she'd kissed him as he died. If she'd had a breath for him. He noticed, as he lay there, that her father's ring, the one she always wore, was on his body's finger. Surely even in that no-man's-land of the process of dying, you are at any given point either alive, or dead? Surely he'd have noticed that ring getting on his finger? 'Third finger left hand, that's wedding-ring finger.' 'Róisín! You did it? You little diamond—you did it without me!' 'Fuck, I hope I was alive for that . . .' 'I mean, I wouldn't miss that.' After a while he laid his hand on his shoulder. He looked at it: there was something unphysical about it. For a moment, it rested on the flesh of his body, then it started to drift slowly through, like honey falling through still water. Nothing linked them, or held them together. They didn't meld. He put his forehead to the back of his skull; felt it glide on the meniscus of it. Pulled back, in horror, at the emptiness. There was no denying it. He was dead. 'What, it's over?' He sat up and stared for a while at the wonder of it. 'So what am I doing here then?' 'No two ways about it, mate—you're a ghost.' He held his arm out in front of him. It was kind of translucent. 'But I don't believe in ghosts.' 'Well, go back and tell that to a scientific survey.' Panic began to rise in him. 'I'm not equipped to be a ghost! I mean, why? Where? Am I to haunt somewhere? Here?' He looked around. 'What, haunt the strip lighting and' 'the hand-sanitizer dispensers? Ghosts need fog and' 'lamplight, creaks and glimpses. Unfinished business, desperate vengefulness.' 'Unfinished business! Well, yes. Obviously. Like, my entire life.' Love this book? Share your review with the Publisher

| |||

| Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri | |||