| Mon

Book Info

Subscribe

| |||

Dear Reader, I saw the local marathon advertised and it reminded me of the year that… It was five in the morning and my husband woke me up. "Suzanne the oven is on, but I can't find the recipe." He wanted to make a batch of my mother's Oatmeal Chocolate Chip cookies. John and Diana, our neighbors, were expecting us to show up at 6 a.m. Today was the Sarasota Marathon and the person in the lead would probably run by their house around 6:30. John called last night and invited my husband and me to watch the race with them. That's when I offered to bring breakfast--"Oatmeal" Chocolate Chip Cookies, but I fell asleep before I got around to baking them. And that's why my husband was up in the wee hours baking cookies. My husband and I are the perfect team. When one of us falls short, the other one steps in and makes up for it. "Suzanne it's time to get up," my husband was softly nudging me. "Where is your mother's oatmeal cookie recipe?" "At my recipe blog, online, Dear." I crawled out of bed and in-between getting dressed to go to the marathon, I mixed the cookie dough and my husband baked. Last year I watched the marathon alone sitting in a lawn chair, out in front of our house, with a laptop resting on my knees. I'd stop working to clap and cheer whenever a runner went by. I stayed put until the end. Cheering for the last, final runner was actually the most important to me. I appreciate the challenge an underdog faces, (from whence I came) and periodically I find myself back in that position. When things are going good for someone, no sweat, who needs a cheering section? It's when your confidence hasn't shown up for a few weeks--or you know you're out of your league--but nevertheless you're determined to try anyway, (everybody has to start somewhere right?) that's when you need clapping and cheering the most. So the four of us, John, Diana, my husband and I, turned into a band of encouragement (literally) for the runners in the marathon. My husband kept the beat going on a drum, I was on tambourine, John had a Didgeridoo (a very long horn that makes deep low sounds) and Diana hooted and hollered for every single runner, "Don't stop now. You can do it!" Our musical cheering section got rave reviews. Marathon runners smiled and laughed, (Even some runners who were making really good time, couldn't help but laugh out loud when they saw us. I worried we might add a few seconds to their finish time). Other runners yelled that we should run behind them and play for the rest of the race, and some of the runners who had turned into walkers--gave us a "thumbs-up," picked up their pace and started sprinting again. And of course we waited patiently for the last runner. A determined woman who had odds and ends hanging from a belt around her waist and there was a helium-filled balloon tied to the end of a broom that she carried in her hand while she was running. I guess she was the "clean-up" crew, a whimsical ending to a magical race. *If you'd like to see a photo of "the band" and the final runner, click here. Thanks for reading with me. It's so good to read with friends. Suzanne Beecher P. S. This week we're giving away 10 copies of the book How To Commit A Postcolonial Murder: A Novel by Nina McConigley. Click here to enter for your chance to win. | |||

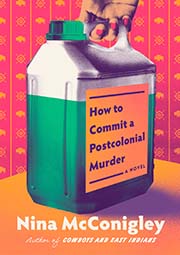

How To Commit A Postcolonial Murder: A Novel | |||

|

PROLOGUE THE BLAME My sister, Agatha Krishna, said it started when they came, and so that's where you could put the blame. But then she said we had to go further back than that. So we blamed it on Reagan; everyone blamed him that summer, the summer the country went into a bust, the summer we watched an exodus empty our town. Then I blamed the Cold War, and Gorbachev—he had the stain on his head, and thus, I felt, couldn't be trusted. We blamed famine in Ethiopia after Amma posted a photo on the fridge of a child with a belly like a hot-air balloon. We blamed AIDS, which we didn't really get, but thought you 'could' get from the water fountain at the public library you stepped on with your foot. We blamed the Olympics and hated Sam the eagle, their feathered mascot, who dressed like Uncle Sam in red, white, and blue, though secretly I had a button of him with his sly smile and torch. We blamed it on my parents for moving to Wyoming in the first place, for settling in Marley. Then we just generally blamed them for everything. We thought they shouldn't have married, that they shouldn't have mixed us up. Shouldn't have made us halfies. Agatha Krishna said we could blame it on our grandparents too, for having one child who went to school and another who stayed at home. For letting Amma wear a crisp, white uniform and leaving Vinny Uncle to read Curly Wee comics. But then she said, "Let's blame it on the British." Everything went back to the British. They did it first, Agatha Krishna said. They were colonists. They were the reason our amma went to school and our uncle stayed home; they were the reason that we were quiet around most white people, the reason our mom drank tea when everyone else we knew, except Mormons, drank coffee. It was the British who shaped Amma's world. That made her spell 'favor' with a 'u,' use a knife and fork, and bake fruitcake with sultanas and nuts. It was the British who taught us to keep our upper lips stiff at all times. That year, we had an Indian summer twice. A frost had come and left the garden in disarray. Tomato stalks broke in two, my mother's peppers dangled like limp green earrings from the stem. But then the days warmed again and an infestation of millers descended. They threw themselves in swarms at the streetlights, marking the intersections. They offered a kind of suttee to the light. Black dots against the Krishna-colored sky. My father, tired from coming off rigs, would fill a large stainless steel bowl with dish soap at night. Leaving it on his desk, he would shine a desk lamp into the soapy bowl. By morning, the bubbles would long have gone flat and the little bodies of the millers would be floating in the water, their wings soaked and black. I always felt bad for them. Drawn to something beautiful, something almost ethereal, only to find themselves trapped. I didn't think it was a good way to die. But what is? And the only way you could justify it was when Amma held up saris eaten to lace, sweaters with holes the size of coins. Years later, I would learn that miller moths don't eat clothes. They're actually great pollinators. We were wrong. Small clothes moths are the real pests. Clothes moths barely fly and don't like the light. But Appa didn't like the sound of the millers hitting the lights at night. Of them clogging the sills of our doors and windows with their downy scales. It was in that second wave of warmth that they came to us. Not tired or wretched or tempest-tossed, but poor. We drove to Denver to pick them up. They did not come off the plane looking bewildered by this new land before them. If anything, they came at us like moths. Fast, a little frantic, and seemingly, as the months would show, drawn to all the wrong things. Amma, who had not seen a member of her family since marrying my father almost fourteen years earlier, ran to her brother, Vinny Uncle, pressed a carton of Marlboro Reds into his pocket, then squeezed my cousin Narayan like a lemon and filled his hands with chocolate. She gave Auntie Devi a rhinestone necklace. We piled into two cars to drive home. Narayan screamed when he saw his first antelope. Auntie Devi stuck her head out the window to catch the wind. Vinny Uncle just remarked on how fast the car went. That we didn't have to stop for animals in the road or pause at scooters packed with bodies. The Ayyars dipped into our lives like a tea bag into the whiteness of a porcelain cup. They muddied the water and made our house feel small, having taken over Agatha Krishna's old bedroom. Now she slept with me. They left rings of talcum powder on the carpet; the bathroom floor was slick with water from their cup and bucket, and the house became smelly with the food Auntie Devi cooked: dosas and sambar, prawns fry and molee. If she wasn't cooking, she stood on the lawn in a sari and cardigan, looking out at nothing. Feeling the air and the altitude with a kind of wonder. Or sometimes she sat in front of the television. She watched a lot of 'Dynasty.' She no longer had her own house; she didn't drive. She had to ask Amma to buy her everything, from underwear to airmail paper. To us, she said little, just cooked us food, then slipped back to the bedroom to watch TV late into the night. She was like Amma. Same long black hair. But not Amma. She was ghost-Amma. The Amma who didn't say anything. The Amma in the room who faded into the furniture. As if she had only half come to America. When you really came down to it, we blamed our uncle. And no matter who started it, we were the ones who had to finish it. So at night, as we lay in bed, Agatha Krishna in a sleeping bag zipped tight to her head, and me under a blanket half-eaten by moths, we told ourselves that it wasn't our fault. She sang a mantra: "The British are to blame, the British are to blame, the British are to blame, and Vinny Uncle will pay." And soon, I joined her'.' We would make him pay. Looking back, though, I'm not sure if that's how it works. I'm not sure you can ever cancel out someone who has taken from you by taking more from someone else. But I think that was the only way we could do it, the only way we could have killed him. The only way we could take our uncle's life and not look back. Not be filled with any blame. 1 YOU But. But before I give you that, before I tell you what happened, I have to give you this. Because you ask for it, I give it to you. Because you don't ask for it, I give it to you. Because you always seem to want to take what I give you and translate it into something else, something that fits your narrative, you can have it. Let's just say it. This story is for you; I know you want it to go a certain way. (continued on Tuesday) Love this book? Share your review with the Publisher

| |||

| Mon Book Info | |||