| Mon

Book Info

Subscribe

| |||

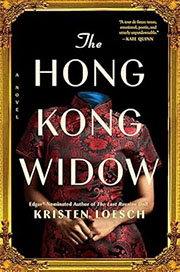

Dear Reader, I've been out of town on business for the last few days. I got home late last night and when I sat down at my computer this morning I immediately realized, "It's going to be one of those days." Nothing about my normal routine seems appealing. I can't for the life of me figure out why, because usually I'm excited about doing my job. This isn't the first time I've had "one of those days". I've definitely been here before--overwhelmed by familiar, simple tasks--can't stay focused, and every couple of minutes my mind goes blank. . . What was I talking about? Yep, it's just gonna be--"one of those days." Thanks for reading with me. It's so good to read with friends. Suzanne Beecher P. S. This week we're giving away 10 copies of the book The Hong Kong Widow: A Novel by Kristen Loesch. Click here to enter for your chance to win. | |||

The Hong Kong Widow: A Novel | |||

|

PROLOGUE SUSANNA HAS HER lips pursed, like she is sucking on sweetroot. I am telling her what it is like to be attacked by an unknown assailant in a darkened room. How it feels to wake up half a day later, your head throbbing, one eye swollen shut, lying flat on a tatami, the straw beneath you turned sticky, your arms stiff at your sides, your fingers bent like you're holding a ball. One of those small spleeny organs that nobody knows about until they lose it-you've lost it. You know it's normal not to be able to recall anything of the attack itself. Normal if you can't picture your attacker; normal if everything is hazy in your head. The problem is that it isn't. Imagine that you remember the events of your attack perfectly-but you remember it all the wrong way around. In your memory you see yourself on the ground, bleeding badly; in your memory you go closer, bending over your own form, your own face. In your memory, you are not the victim. You are the attacker. "Uh- huh," Susanna says, jotting something down on her handheld electronic screen. Susanna Thornton is an award-winning author of narrative nonfiction, known for her interest in murky historical mysteries, particularly crimes. Why else has she sat me down like this, if not for a story such as this one? Her initial request for an interview was shocking; her voice on the phone was clipped and stern and gave nothing away. But she can't just want the usual bland impressions of the decades I have lived through, the Japanese occupation of Shanghai, the Pacific War, the Chinese Communist Revolution. I want her to want more. I want to see her innate curiosity piqued. I want to hear her laugh openly at me. I want her to tell me that it's impossible, what I have just said, all while her mind spins with possibilities. But it seems she has little concern for the darkened rooms of my life. * * * "THAT HAPPENED BACK in Shanghai?" says Susanna, but it's not quite a question and she doesn't wait for an answer. "I don't want to waste your time—I'm here to ask you about Hong Kong. About Maidenhair House." For a moment it feels as if I am waking up half a day later, all over again. "I'm sorry. I must have misheard you," I say. "Maidenhair House," repeats Susanna, whose voice is very clear, whose voice regularly carries over the heads of hundreds of people. "About the late-summer night in 1953 that's turned into an urban legend. About the alleged massacre. About how, when the police were called to the scene, they couldn't find a trace of it—and later called it a collective hallucination." "Then what is left to say?" I ask, but perhaps she can hear my heart beating slightly faster, louder than my words. "It's been confirmed that several young women went up to the house that night and were never seen again," says Susanna. "Women who were refugees of the Revolution. Women with no family or friends. Women that nobody would have missed. I've spoken to some Canadian urban explorers who spent a night at Maidenhair about fifteen years back now," she adds, with a hint of satisfaction, "and I got one of them to admit that there was indeed blood. When they went over it with luminol, they found blood 'everywhere'. Walls. Floors. Rugs." She says this like it is a revelation, blood beneath your feet. Maybe in this country it is. But in the place I come from, the dirt is always red, if you dig deep enough. The balloon-whistle of the espresso maker sounds from another room, but Susanna doesn't budge. She thinks the silence will force me to speak. She sweeps her long mat of hair behind her shoulders. I have thought of other things to talk about by now: perhaps about the time my mother forced me to sell my own hair to a visitor to our village who was trying to add to his collection of female braids; how much I wanted to refuse; how, if I were not so tragically proud, I might have begged. But we needed the money and in the end Ma got her way. She cut it just above the jaw. "I intend to solve it," says Susanna. She can get my hair back for me? Even if by now it is scattered across China like ashes? "I'm going to uncover the truth about that night," she insists. I am not sure this is an interview so much as it is a sounding board, because clearly the story she wants to tell is already formed in her head. I can see it shining in her eyes. "I'll do it with your help or without it, Mama, but I'm going to find out what happened at Maidenhair House. And I'm going to find out why 'you' got away." PART ONE 1 SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 2015 SUSANNA'S DINING TABLE is long, meant for more people than just me and her. At every place setting there is a plate and enough slim silver cutlery that I could make a traditional Chinese cutting of the tablecloth; it is an eerie scene. Once there were three eating at this table every day, of course: Susanna; Peter, her first husband; and Liana, my granddaughter. Then came the divorce; then there were two. Then Susanna married Dean, and there were three again. Then Liana left for college. Then there were two again. And now Dean is gone. I am here tonight, but my daughter acts like she is alone. SUSANNA SITS ACROSS from me, reading on her phone, her eyes moving visibly beneath the lids. All the food on the table has just been taken out of the fridge. I take a sip of my tea. It is hard and gritty. "Something wrong, Ma?" she asks. "It's so cold in here, that's all. Did you take this whole house out of the fridge?" A short sigh. "You didn't have to stay for dinner." How could I go, after the conversation we have had? I had not thought about Maidenhair House in several decades, but now the memory burns brighter than the light overhead. Susanna, naturally, does not see the effect her reminder has had on me; she thinks Maidenhair is like any other murder mystery she has ever encountered, gone rancid with time. I wonder how she learned that I was there that night, but it surely involves more devices, more squinting, more poorly lit rooms. I imagine a list of women's names, one after another. I imagine Susanna struggling to make sense of it, and in the end, believing what she sees. The greatest surprise is not her discovery of my presence, nor her self-proclaimed investigation. The greatest surprise is that my daughter has gotten out of bed. She has hardly left the house since Dean died, three months ago. "Yes, I was at Maidenhair," I say, and her eyes widen. "But I have never spoken of that night to anyone. Not because I have something to hide, but because I have had no desire to turn over the past like the dirt of a grave." It has the effect on her that I hoped for, and simultaneously dreaded: Susanna sets down her phone and diverts her full attention to me. "But you're willing to talk about it now?" she says. I notice that she hasn't picked up anything to eat with; she has become as skinny as a bamboo stake. "If you do something for me in exchange." "What is it?" "I want you to find out why I remember being attacked, so many years ago, from the perspective of my attacker." "The thing you described earlier, you mean?" "That is my condition." "Forgive my bluntness, Ma," she says wearily, "but I'd say it was a trick of your imagination. Your brain trying to protect itself from whatever happened. But if you want me to find out who attacked you, I suppose we can try. 'When' was it? Not when you were growing up? Because 1930s Shanghai, we're talking Japanese soldiers, gangsters, drug dealers, criminal overlords," she says, like I might not know, like I wasn't there. "It might be difficult to—" "I didn't say 'who'. I said 'why'." (continued on Tuesday) Love this book? Share your review with the Publisher

| |||

| Mon Book Info | |||