| Mon

Book Info

Subscribe

| |||

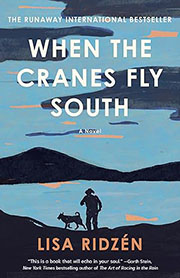

Dear Reader, Happy Labor Day! If you live in the U.S. hopefully you get to celebrate today's holiday. After you finish eating grilled hot dogs, burgers and brats, how about starting to work on your entry for this year's Write a DearReader Contest? There's a story inside of you, and I can't If you love to write, or if you've never written anything, but thought about it--give it a try. Hundreds and hundreds of readers enter the contest every year and it's interesting, because at the end of many of the entries, there's a note--"Even if I don't win, I had fun and it felt good to write this column. Thanks for the opportunity." I'd love to read your entry, so please don't be shy. All the info on prizes, for you and your library, deadlines, guidelines and even last year's winning entries are here. Thanks for reading with me. It's so good to read with friends. Suzanne Beecher P. S. This week we're giving away 10 copies of the book When The Cranes Fly South: A Novel by Lisa Ridzén. Click here to enter for your chance to win. | |||

When The Cranes Fly South: A Novel | |||

|

I fantasize about cutting him out of my will, making sure he doesn't get a penny. He claims it's as much for my sake as Sixten's that he wants to take him away. That old men like me shouldn't be trudging about in the woods and that dogs like Sixten need longer walks than a quick stroll to the road and back. I look down at Sixten, who is curled up beside me on the daybed. He lets out a big yawn and gets himself comfortable with his head on my belly. I dig my swollen fingers into his coat and shake my head. What does that idiot know, anyway? There's no chance in hell I'm going to let him get his own way. At the kitchen table, Ingrid sighs. "I can't promise anything, Bo, but I'll do my best. Because this isn't okay," she says, scribbling away in the carers' logbook. I nod and give her a faint smile. If there's anyone who can help me with Sixten, it's Ingrid. The fire crackles, and I struggle to tear my eyes away from the flames dancing around the birch logs. My thoughts drift back to the conversation I had with Hans this morning, and I feel myself getting worked up again. Who does he think he is, our son? It's not up to him to decide where Sixten should live. I close my eyes for a moment, tired from all the anger. I listen to Ingrid's movements, and my breathing slowly grows heavier as the rage subsides. In its wake, I'm left with the same niggling feeling I've had quite often lately. A clawing that comes and goes in my chest. A sense that I should be doing things differently. "God, you've become a real brooder," Ture said on the phone one day recently, when I tried to explain. He's probably right, I think now, lying here beside Sixten and listening to Ingrid pottering about. Because in the void you left behind, Fredrika, I've started thinking about things I never paid much notice to. I've never been one to doubt myself, always known what I want and been able to tell right from wrong. I still can, but I've also started to wonder. I've started to wonder why things worked out the way they did. To think about my mother and my old man in a way I never have before. But more than anything, I've been thinking about Hans. I don't want things between us to end up the way they did with my old man. It's just that all his nagging about Sixten makes me so angry I don't know what to do with myself. I won't be able to fix a single bloody thing if he takes Sixten away. "I'll go for a quick walk with him at lunch," Ingrid says as she firmly closes the logbook. Her eyes flash. She has a dog of her own, and just the thought of them taking Sixten away upsets her. She runs a hand through her short gray hair and picks up my pill organizer. Checks that everything is right. For my heart, and all the rest of it. "Thank you," I say, taking a sip of my tea. If we'd had a daughter, I would have liked her to be Ingrid. She was in the same year as Hans, and her grandfather worked at the sawmill in Ranviken at the same time as my old man. She wasn't wearing a jacket when she arrived today, just the navy fleece with the home-help company's logo on the chest, and I can't believe she's not cold. That sort of thing always surprises me nowadays, that no one ever seems to feel the cold. I used to go without socks for half the year, and I'd be in shorts from the start of May, but these days I'm freezing all the time. The doctors and carers tell me that's just what happens. That it's normal. It doesn't matter that the weather is getting warmer—I'm going to keep lighting the fire. You've always been a delicate soul, Fredrika, shivering at the slightest chill. They usually have you wearing one of your old woolen cardigans whenever we come to visit. Ingrid frowns, and I think I hear her mutter something about the prepackaged pills. One day, she'll start shivering like an ema- ciated snipe, too. She double-checks the organizer one last time, then takes out her phone to see if anyone has called. It strikes me that I don't know whether she has a family of her own—or have I just forgotten? I've noticed from the way people reply to my questions that I'm getting forgetful. It really seems to bother Hans. "You just asked that," he always snaps. Ingrid never makes me feel silly like that. I study her as I shift my legs, stretched out on one of your old patchwork quilts. I'm sure she has beautiful children. Friendly and well raised. I reach for the glass of rose-hip soup she left on the table ear- lier and drink a big mouthful of the cool, thick liquid. Rose-hip soup is one of the few flavors I still enjoy. So many other things taste different nowadays. I can't eat cream cakes anymore, for example, because they taste like mold, but Hans still insists on buying them. "You're getting so thin," he says. As though it's my fault my muscles are wasting away. As though I invented the aging, useless body. I set the glass back down on the table and use my lower lip to suck the soup from my mustache. Ingrid goes over to the stove and adds a couple of logs. She knows what she's doing. She and that brother of hers actually have a firewood processor, the kind that can cut and split the wood. Twelve tons it weighs. I didn't know her parents, but I know who they were. Both died early, and Ingrid took over the family farm. Some of the other carers have no idea how to light a fire, and they always put the birch bark at the bottom rather than building a stack and lighting it from the top. I used to correct them, but after a while I got sick of doing that. The young ones in particular feel like a lost cause. There's plenty I could say about my old man, but at least he taught me how to light a fire properly. Young people today, they don't think any further than tomorrow. They get everything served up to them, and they can't do any of the things we learned as kids. What would they do if something big happened? If the power went out, or the water supply failed? They'd collapse like a house of cards, the lot of them. My gaze comes to rest on the fire again. I think I'd probably be able to last a good while on water from the stream, burning logs in the stove and eating the food in the basement. The flames nibble tentatively at the birch bark and quickly grow into a raging blaze. The flickering yellow glow makes me think of Hans and the way he used to sit transfixed in front of the fire as a boy. Back when he still looked up to me and pricked his ears at everything I said. "Hans says I should stop using the stove, too. He doesn't just want to take Sixten away; he wants to take my wood as well." I chuckle, though the familiar clawing feeling in my chest is back. "He thinks I should just turn the radiators up instead, that I can afford it." "I know," Ingrid replies, rinsing off a plate. "But it's from a place of concern, you know that. He's worried you might forget the damper or fall while you're bringing the wood in, while you're out with Sixten." Or maybe it's just selfishness and pigheaded idiocy, I think, though I bite my tongue. "Just forget about the wood, Bo. We're here so often that if you need anything, we'll realize soon enough." I reach up and touch my beard, mutter that Hans doesn't give two hoots that they're here to help, but Ingrid doesn't seem to hear. "It'll be Eva-Lena this evening," she says after a while. I feel a rush of anger and nod with my eyes closed, but I know sleep will have me in its relaxing grip before long. Eva-Lena started coming over when Ingrid slipped on the first ice and broke her foot. She was off work for weeks, which meant I had to put up with that battle-ax instead—and as if that weren't enough, she's from Frösön. They visit me four times a day, the home help. When Hans first broached the idea, about six months after you left, I thought it was ridiculous. I laughed in his face, in fact, though I did feel bad afterward. He meant well, I suppose. This was back when I was still in control of my own life. (continued on Tuesday) Love this book? Share your review with the Publisher

| |||

| Mon Book Info | |||