| Mon

Book Info

Subscribe

| |||

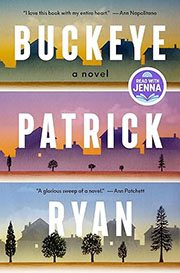

Dear Reader, Simply share a story, win some cash, buy some darling new shoes or a fishing pole, and impress your friends and family. Sound like fun? It could happen to you, but first you need to enter my annual Write a DearReader Contest. You don't need to be a writer to enter. The contest is writing for fun. To read last year's winning entries and information about the rules and deadline, click here. I filled out a New Patient form in a doctor's office the other day and one of the Tell-Me-About-Yourself questions was, "What's the biggest cause of stress in your life?" My answer: Me. It was an instantaneous response. At first I was kind of amused, 'That was a good one Suzanne, pretty funny.' But then when I started to cross out "Me" and tried to think of a "real" answer, I realized that I had it right the first time--and that was a little scary. I didn't want to seem like a nut when the doctor reviewed the form, so I considered some other multiple-choice answers. A.) Work. Okay, work is stressful sometimes--and why? Well, let's see, there are deadlines, but then again, maybe "Me" has just a little bit to do with the stress in my work. I'm my own boss, I set most of my own deadlines, so exactly who is stressing me? B.) My husband. Yeah, there must be something that he does to cause stress in my life. Let's see, he gives me a foot rub every night, encourages me in any new thing I want to try, and is constantly telling me to lighten up on myself. That doesn't sound stressful to me. So what's up? Why does this stress keep following me around all the time? Wherever I go it seems to be there. Hmm. Maybe that's a clue. Thanks for reading with me. It's so good to read with friends. Suzanne Beecher P. S. This week we're giving away 10 copies of the book Buckeye: A Novel by Patrick Ryan. Click here to enter for your chance to win. | |||

|

PART I Chapter One Cal Jenkins was born in the spring of 1920 with one leg shorter than the other. Just two inches shorter, but that was enough to make plenty of things difficult. Balancing on a bicycle took twice as long for him to learn as it did for other kids. Track and field was out of the question. So was walking without a pronounced limp or going up and down a set of stairs without securing himself on the railing—until his father, amateur carpenter and junk collector, improved Cal's condition by carving a new, thicker sole out of tire rubber and nailing it onto his left shoe. At school, boys made fun of the way Cal walked, then made fun of the shoe with the extra- thick sole (someone noticed within an hour of the first day he wore it). But one boy—flush- cheeked and small for his age—pulled Cal aside during morning assembly and told him he was unique in God's eyes. "I know," the boy said, "because I am too. I can't touch my toes, you see. I have unusually tight hamstrings." He bent over to demonstrate, and his fingertips barely reached his kneecaps. "We're each meant for a special thing," the boy said, and when Cal asked what his special thing was, the boy shrugged and said the two of them would have to wait to find out. What they found out—separately, and years later, after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and threw the country into a panic, after young men stopped waiting for their numbers to be drawn and began to volunteer—was that having one leg two inches shorter than the other was enough to make a person unfit for military service, while having unusually tight hamstrings wasn't. That boy, Sean Robison, was sent from Ohio to Mississippi for basic training, and was then sent to Tunisia, and from Tunisia to Sicily, and from Sicily to Germany, where he was shot through the neck in the Hürtgen Forest while reloading his rifle and reciting the Lord's Prayer. Cal remained in his hometown and got a job in a concrete plant. He read comic books and adventure novels into his twenties. He married a local girl named Becky and eventually went to work in her father's hardware store. Sometimes he wondered if he would ever discover what his "special thing" was—his purpose, he'd decided—especially in the face of a world war that wouldn't have him. He was so conscious of not being overseas that he found his limp worsening all by itself. He told people about his leg, people who hadn't asked and didn't care. Sometimes he even pointed to his shoes, ordered now from a medical supply company in Dayton. "My condition causes hip problems," he'd say. Which was true, though he had yet to experience any. Bonhomie had been founded in a northwest pocket of Ohio in 1857 by a small group of merchants and their families, on land transformed by the Last Ice Age, when a glacier nudged its way down from Canada and melted, creating not only Niagara Falls and the Great Lakes, but also a vast swamp across the top of Ohio and Indiana that took thirty years to drain and left behind soil densely ripe for farming. The town was built with local lumber, shale, and limestone, and with granite from North Carolina, marble from Vermont and Colorado, and steel from Pennsylvania—all of it brought in by rail. For a time, the town was a grid of nine streets, four running north–south and five east–west. The population grew from within as much as it could manage, and from without as much as it needed to. It swelled with migrant workers and their families during harvest time—corn and wheat and tomatoes and sugar beets—and shrank again when the workers moved on. Others moved into the area for the jobs created by the factories that sprang up around Hancock County. Immigrants from Italy, Austria, Hungary, Poland, Russia, and many other countries were processed through Ellis Island and absorbed by the cities and towns of the east, though some went west—and some of those stopped and settled down in Bonhomie, which seemed as good a place as any. Over time, the original grid became known as downtown, and what wasn't downtown became known as neighborhoods. Not sections, which would have suggested clear dividing lines and the need for those lines, but general neighborhoods that took shape as people found their people. There were well-to-do neighborhoods and poor neighborhoods, and there were all the neighborhoods in between. There was a neighborhood called Tiller's Flat, where several Mexican families and nearly all the Black families in town—less than a dozen—lived, many of whom had moved from the South for the industry jobs (and to get away from the South). There was a neighborhood of apartment buildings and bungalows called Chesterton that was made up mostly of migrant families from out west, and a neighborhood situated between the two synagogues that was thought of as mostly Jewish. When people wanted an Irish neighborhood to point to, they could always refer to the block with St. Catherine's and Good Shepherd School as Vatican City. And scattered throughout these neighborhoods were all the people who didn't think they belonged to any group, most of them Protestant. By the time the U.S. got into the Second World War, the population of Bonhomie had topped six thousand. The town had its own police force, fire department, and vocational college. It had two dozen restaurants (if you counted coffee shops and soda fountains), five banks, four dry cleaners, two record stores, and a movie house. Industry thrived in and around town, such as J & J Concrete, Tuck & Sons Aluminum, and the Mid-American Canning Company; and industry died, such as Ingleton's Fizzy Pops, Dilco's Feed & Supplements, and the Hancock Bell & Skillet Company. There was a horseshoe-shaped lake with a fetch of a quarter mile just south of town off Route 18. To the north, where the exit ramp off Cooper Road fed onto Highway 23, the neon Tuck & Sons tulip—twenty feet in diameter, pink and flat as a stencil—stood atop a hundred-foot pole, visible for miles. A rusted grain elevator still bearing the checkered Purina logo loomed like a monolith at the east end of Main Street. Passenger and cargo trains came through town day and night, and some of them stopped to deposit or collect people and mail and goods, but most of them bypassed the railyard and the station and town altogether. Bonhomie wasn't nearly so small that everyone knew everyone else, but it was small enough that, sooner or later, most everyone felt as if they'd laid eyes on most everyone else. Since the start of the war, fewer and fewer young men were seen on Main Street. Meanwhile, there was no shortage of old-timers—fifty and up—who'd fought in the last big war. One who'd lost an arm and wore his sleeve pinned, another who got around on wooden crutches because one of his legs had been blown off just below the knee. Cal's own father had been awarded a Purple Heart for taking a bullet through his shoulder while pulling a wounded officer into a foxhole in the Meuse– Argonne—though the medal was not to be seen in his increasingly cluttered house and he didn't want to talk about his war days. Cal was astounded by the impact two inches of leg could have on a person. Being deprived of those inches, he'd gained what seemed to be a full and healthy life. But feeling happy about it didn't seem right—not when a million young men were inducted during the first year America got into World War II, and ten million by early May of 1945. That Tuesday morning, Cal had just opened Hanover Hardware on Sutton Street and was sitting on a stool behind the counter, sorting a box of washers, when a woman walked in and asked if he had a radio. Her forehead was high and her red hair was done up in Victory Rolls. Her mint-green dress and matching pillbox hat, her white gloves, and her coral lipstick suggested money to Cal. Her eyes latched on to his as she crossed the linoleum floor. He told her yes, the store had a Zenith, but it wasn't for sale; it was in the office. She asked where the office was. "Basement," Cal said, nodding toward the stairs just past the end of the counter, and without another word she walked past him—right past the handwritten sign that read EMPLOYEES ONLY—and started down the stairs. "Ma'am?" Cal said. He dropped the washers into the box and followed her. The basement was used mostly for overstock—though there hadn't been much to store in the past few years, with production focused on the war effort. Cal caught up with her as she made her way between two tall sets of half-empty shelves. He indicated the area in the corner that the store's owner, his father-in-law, Roman Hanover, had designated as the office. Across from the cot where Roman took his naps was a pint-size desk where they did paperwork and where Cal ate his lunch, listened to radio programs, and read adventure novels. He was currently halfway through 'The Bold Buccaneer'. He tugged on the string for the overhead bulb, and in its glow he noticed the deep jade of her eyes and saw how pronounced her cheekbones were, giving her face a V shape over the smooth stem of her neck. She was beautiful, he realized. But she looked agitated, impatient. She motioned toward the radio with one of her gloved hands. "Why isn't it on?" He switched on the Zenith, surfed the wheeze and static for whatever she was hoping to hear, and within seconds he found it: Truman, informing the country that Germany had surrendered to the Allied forces. It was the announcement everyone had been anticipating. Hitler had been dead for a week. The Nazis had surrendered the Netherlands to the British five days earlier. Still, the news was breathtaking. Through the hopper window that opened onto the street they heard shouts and whistles. A car horn tap-tap- tapping. Then another, and another. "Jeez," Cal said. "Can you imagine what it's like in Berlin right now? I probably would've been there, if it weren't for…" He wobbled his shoe with the extra-thick sole. But she was looking at the caramel-colored radio. Her eyes were glistening. "Do you think—" she said, then paused as if unsure of what she wanted to ask him. She took a breath. "Do you think people will start coming home?" "From Europe? I hope so. But Hirohito's still giving us a run. They might send those guys over to the Pacific." The woman blinked against the sting in her eyes and, as Truman continued talking, looked at this hardware store clerk who, when he'd been sitting behind the counter, had been almost handsome with his gray-blue eyes, his wavy blond hair that looked as if he'd just raked his fingers through it, his narrow jaw, and an early set of lines framing his mouth. Now that she could see all of him, he was still almost handsome but in a different way. He wasn't very tall, and his stance was off, his hips pitched at an almost uncomfortable- looking angle. His gold-and-black-striped tie was tucked between two buttons halfway down the front of his oxford shirt and looked wrong that way; she wanted to pluck it out. Instead, she took him by his shoulders, pulled him toward her, and kissed him. Cal would have gasped if his lips weren't against hers. They kissed until Truman finished speaking. When they stepped back, she turned off the radio. He heard her sniffle, offered her his handkerchief. She touched it to the outside corners of her eyes as she glanced at the cot and pint-size desk, the brown bag with the apple beside it, the library book with the swashbuckling cover. "Does a child live down here?" (continued on Tuesday) Love this book? Share your review with the Publisher

| |||

| Mon Book Info | |||