| Mon

Book Info

Subscribe

| |||

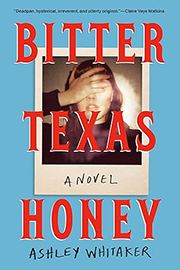

Dear Reader, Driving down the road last weekend, I passed by a boy and his dog sitting behind a card table with a sign taped to it. I couldn't read the sign, but I could see a jug of lemonade and cookies. It was a cold morning here in Sarasota, Florida, too cold for a casual glass of lemonade and I started to worry the boy wouldn't get much business. I knew I only had a couple of twenty dollar bills in my wallet, so I turned around and drove back home to retrieve some lemonade money. I try to stop whenever I see a kid's lemonade stand. When I was a young entrepreneur, my lemonade stand turned into a booming little business. My father worked as a mechanic at the car dealership right behind our house. In the summer, it got pretty hot in the non-air conditioned garage, so Dad and the other mechanics became regular customers. Pockets filled with lemonade money, my husband offered to take a stroll with me, to what I thought was a lemonade stand--but it wasn't. Instead of LEMONADE 25 cents a glass, the sign read: "Free Lemonade and Cookies. Donations to the Humane Society Accepted." A serious, sincere, 12-year-old boy, along with his dog Samuel (who had been adopted from the Humane Society) was doing a good deed--and having fun, too. Not only could folks get a free glass of lemonade and a cookie, there was a tall jar of dog biscuits on the table, "You can give Samuel a dog biscuit, too! Go ahead, it's fun!" Fun indeed and such an inspiration--a 12-year-old boy (who decided on his own), to do what he could to help other dogs like Samuel. Thanks for reading with me. It's so good to read with friends. Suzanne Beecher P. S. This week we're giving away 10 copies of the book Bitter Texas Honey: A Novel by Ashley Whitaker. Click here to enter for your chance to win. | |||

Bitter Texas Honey: A Novel | |||

|

1. CANON Conservative talk radio hosts were the most reliable men in her life. Monday through Friday, no matter what she'd gotten into the night before, they were there, like old friends and confidants, like second fathers, like faithful lovers, their voices booming and authoritative, clever and jovial and worldly, always ready to soothe her mind and silence her thoughts. Joan listened one morning, in January 2011, while she got dressed for her internship, tucking a button-up blouse into control-top pantyhose, sliding on her black pencil skirt, and dry heaving into her sink. She continued listening as she walked the four blocks uphill to the Texas Capitol, her head throbbing, chugging a sugar- free Red Bull, with two more cans clanking in her purse for later. She listened intermittently throughout her five-hour shift as she tried to piece together the events of the night before, reading through a thread of unsettlingly intimate text messages between her and a man saved in her phone only as "Marine—Dirty 6th." She resumed listening as she packed up her things and left, heading to a coffee shop near campus, where she intended to work on her novel. Because more than anything else, Joan West was still a writer, or at least she hoped to be. She walked in the harsh cold, earphones in, a lobbyist-gifted scarf wrapped around her neck. Her favorite host, Dennis Prager, was talking again about the inherent differences between men and women. Every Wednesday, Dennis dedicated his entire second hour—called "The Male/Female Hour"—to traditional gender roles and healthy marriages. Even though Dennis was already on his third wife, Joan trusted his advice wholeheartedly. He seemed so wise and confident, often citing his experience counseling young couples as a rabbi. By listening to his show, Joan hoped to uncover the mysterious reason she always failed in love. Dennis insisted that the Left was working hard to destroy America by downplaying the obvious, natural differences between the sexes. Joan would have thought he was being paranoid if she hadn't experienced it herself. During her first semester of college, at the University of Miami, Joan learned in Sociology 101 that there was no real difference between men and women. Rather, she had been 'socialized' by the patriarchy (and her parents) to like pink, to play with dolls, to become clingy after sex, etc. Learning this, Joan tried hard to free herself, to embrace her inner manliness. She went braless in dinosaur T-shirts, stopped shaving, and cut her hair short. She went to drum circles on South Beach, topless, and kissed girls. She had emotionless sex with her platonic guy friends, mostly student musicians in the jazz program. She wrote ultra-minimally, like Ernest Hemingway or Bret Easton Ellis. But instead of making her feel empowered or fulfilled, Joan's behavior only led her to an amphetamine-induced manic episode, a forced year off from college, and an HPV diagnosis. When Joan reached the Drag, Dennis was explaining that women's denial of their God-given nurturing roles and attempt to enter the man's sphere had led to an entire generation of depressed women and confused men, which, passing by a bus stop full of miserable-looking UT students, Joan felt was a compelling theory. Now that Joan was aware of this omnipresent, nebulous mass called the Left and its nefarious motives, she was on alert for it at all times. She passed by the iconic "Hi How Are You" frog mural, then the Church of Scientology, where a cluster of redheaded runaways known colloquially as "Drag rats" were gathered with their dogs, playing banjo and fiddle music, wearing dirty army fatigues, probably high on heroin. One of the Drag rats approached Joan, demanding money. She ignored him, turned up Dennis Prager, and walked faster. Dennis was certainly right about one thing: Something was seriously wrong with her generation. She entered Caffè Medici, her cheeks flushed from the cold, and went to the bar, where her favorite barista, Roberto, was working. She removed her earphones and scarf and set her phone face down, careful to conceal the screen from him, lest he get a glimpse of what she was listening to. She ordered a glass of red wine, pulled Ernest Hemingway's collected stories out of her book bag, and began reading with the cover prominently displayed. Every couple of minutes she used a mechanical pencil to mark passages that felt important or profound. "What's up, lady? What are you reading?" Roberto asked, setting the wineglass in front of her on top of a napkin. "Oh, I love that book." Joan had first met Roberto while she was studying for finals the month before, in December, shortly before graduating from UT. They rarely spoke, but he possessed a mysterious, subdued earnestness toward life that intrigued her. He called her "lady," which wasn't anything special. He called all the female patrons "lady." "You've read this?" Joan asked. "Of course. The second story is the best one in there. I love the part where the guy bleeds to death after getting impaled by that fake bull." "I love that part too," Joan said, straightening in her seat. And this was true, from what she could remember of the scene. She hardly remembered much of what she read, perhaps because she was usually high. But she did recall that particular image: the man in Spain dying in a pool of his own blood. She watched Roberto as he made a latte. He was wearing the same jeans he always wore, and a pearl-snap cowboy shirt that was at least a size too small and barely grazed his belt line. Joan wondered if it was meant to be a woman's shirt. She took a large gulp of bitter wine, hoping her heart would begin to beat more slowly. Joan had chugged all three of her Red Bulls during her shift at the capitol, where she was a legislative intern for one of the most conservative members of the state house, an ex-cop from Houston with tall crispy hair who wore yellow alligator-skin boots every day. The boots had been a personal gift from Governor Rick Perry, she was often reminded. The job began earlier that week and would last through May. The legislature in Texas only met once every two years. Even though the job was unpaid, it was extremely easy and made her feel that she was one step closer to adulthood. It also greatly appeased and impressed her family, who had agreed to continue paying her exorbitant downtown rent. Halfway into her first glass of wine, Joan ordered another. After Roberto finished serving his other customers, they continued to talk about literature. To her surprise, it seemed as if Roberto had read every book ever written. There was nothing Joan had read that Roberto hadn't, and she began to feel inadequate. She was on her third glass when she revealed that she was a fiction writer, and Roberto told her that he was too. They exchanged email addresses before she left and vowed to start sending each other stories. Roberto's first email arrived later that night. Joan was sitting crosslegged in an orange velvet chair, smoking black resin out of her pink pipe, waiting for her dealer to arrive with fresh weed. The email was short and contained a link to his story "Moshing Towards Bethlehem," which had been published the previous fall in an obscure online journal called Possum Stinkdom. Joan felt mildly ashamed that she didn't have anything published to share. She skimmed a few paragraphs before getting distracted, her mind consumed by thoughts of what she should send Roberto in return. She wanted to impress him, to appear as prolific and assured as he was. "What do you think I should send to this writer guy?" Joan asked her roommate, Claire, who was standing at the window, drinking chardonnay, watching a concert through the blinds. Of Montreal had just started playing on the outdoor stage at Mohawk, one of three music venues next door. The bass was so loud it shook the entire building. The laminate floor vibrated. The dishes rattled in the cabinets. Claire stood for a moment, considering. "What about something with your dad? That material is always pretty strong." "That could work, I guess," Joan said. She mostly respected Claire's opinion. They had met at Oxford two summers before, during a Jane Austen study abroad through the UT English Department, where they drank more, and more often, than any of the other girls in the program. Claire was also a writer, working on an epic one-day novel in the style of Ulysses. Claire did a ballerina move into the kitchen, where she picked up her oversized wine bottle sitting half empty on the counter. She filled her glass nearly to the brim, then topped it off with a dash of sparkling water. Claire did this, she often explained, to "pace" herself. She walked back into the den with her glass and examined her profile in Joan's full-length antique mirror. "I hope I threw up last night," Claire said, sucking in and placing her hand on her lower stomach. "I'm pretty sure you did," Joan said. She opened her laptop and began searching her chaotic desktop for the latest draft of her comingof-age novel, 'Cowgirls and Indians', which she'd begun writing in Miami, and from which she would extract an impressive stand-alone piece about her dad. Opening the document increased her heart rate and shortened her breath. The muscles in her chest and neck tensed up. As much as Joan wanted to be a writer, she didn't actually enjoy the process of it, and hadn't since she quit Adderall three years before, at the behest of her parents. Without amphetamines, Joan wasn't sure why she bothered with writing. It was as if she was trying to fill some deep void, the origins of which she chose not to explore. "Are you coming out tonight?" Claire asked. "Luke's playing at Cheer Ups." Luke was Claire's on-again/off-again boyfriend of four years. "Not tonight," Joan said. "I'm pretty tired." The truth was that her dealer would be over any minute, and she didn't want to miss his delivery. "Fine. Let's at least get a picture," Claire said. The girls took a stoicfaced selfie and posted it to Facebook, with the caption "Great American Novels Coming Soon." Claire left, her dealer came and went, and Joan remained in her chair with her laptop open, Roberto's story languishing on the screen, unread. Joan smoked a second bowl while looking out her windows, admiring her view. From her corner apartment, she could see so much: the top tip of the capitol, the skyline, the sleek-looking homeless shelter. She zoned out for a few minutes, entranced by Club de Ville's blinking, crown-shaped sign directly across the street. Feeling high and renewed, Joan wrote a quick response to Roberto. This was amazing, she wrote, even though she hadn't finished reading his story. Love the homage to Joan Didion. Very subversive. Thanks, lady, he replied ten minutes later. That really means a lot. Hope to see something of yrs soon. (continued on Tuesday) Love this book? Share your review with the Publisher

| |||

| Mon Book Info | |||