| Mon

Tue

Wed

Thu

Fri

Subscribe

| |||

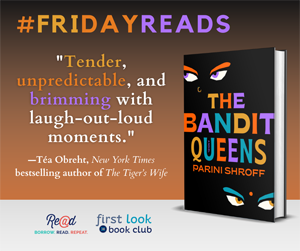

Dear Reader, It's my pleasure to share another Honorable Mention column from this year's Write a DearReader Contest. Today's piece was written by Teresa Fronek. Thank you for your entry, Teresa… Topsy Turvy – Teresa Fronek Thanks for reading with me. It's so good to read with friends. Suzanne Beecher P. S. This week we're giving away 10 copies of the book The Bandit Queens: A Novel by Parini Shroff. Click here to enter for your chance to win.

| |||

The Bandit Queens: A Novel | |||

|

(continued from Thursday) Geeta left then, her heart flapping as she tugged her earlobe. She walked in the littered alley behind the shops. It was not the most direct way home, but it provided cover. If Samir left Karem's, he'd spot her immediately. That thought made her run, her empty bag bouncing against her like a numb limb. Geeta was not accustomed to running; with each step Samir's threats slalomed in her head. Would he just beat and rob her, or kill her? Would he rape her? When shock gave way to anger somewhere around the Amin shanty, she changed her physical and mental path. That drunk 'chutiya' thought her hard work, her life of carefully preserved solitude, was an open treasure chest for his convenience. The Bandit Queen wouldn't stand for it; she'd killed the various men who'd brutalized her, starting with her first husband. After she joined the gang, she returned to his village and beat him and his second wife, who'd harassed and humiliated Phoolan. Then she dragged him outside and either stabbed him or broke his hands and legs, Geeta had heard differing stories. Phoolan left his body with a note warning older men not to wed young girls. (That last bit might've been untrue, as Phoolan Mallah was illiterate and knew only how to sign her name, but it made for excellent lore, so no matter.) The point was: if the Bandit Queen caught wind of burgeoning betrayal, she wouldn't wait to be wronged. A gram of prevention was worth a kilogram of revenge. By the time Geeta reached Farah's house, her throat was dry and she needed a cool bath. Still, she was certain she'd beaten Samir there and pounded on the door. While waiting, she cupped her knees with her hands and panted. Crickets chirred. Her pulse thrummed to the beat of, irritatingly enough: 'kabaddi, kabaddi, kabaddi'. "Geetaben?" She had to suck in two gulps of air before she could manage to say: "I'm in." THREE It was after ten when Geeta heard someone approach. Solar lantern in hand, she opened the door before Farah could knock. Without the lantern, it was as dark inside as it was outside. The scheduled power cuts ("power holidays" they called them, as if it were a rollicking party to grope in the dark and knock your knees on furniture) were increasingly longer and less scheduled. They'd all grown up with kerosene lamps and candles, but after many fires, NGOs came into their town with a rush of concern and gifts, like lanterns and the larger solar lights installed in the more trafficked portions of the village. Farah stood in the dark, her thin elbow at a right angle, hand still lifted. "Oh, hi!" she chirped, as though they'd bumped into each other at the market. She had, Geeta noticed, a rather uncharming habit of finding amusement in everything, even premeditated murder. Farah rubbed her hands together and a clean rasping sound filled Geeta's home. "So what's the plan?" Which was exactly the question that had been squatting on Geeta's head for the past few hours. Farah was counting on Geeta's one-for- one score in the murder department, and Geeta had long ago stopped protesting her innocence. Telling someone the truth was asking them to believe her, and she was done asking for anything from this village. Because Geeta saw no reason to reveal the truth now-how hard could it 'actually' be?—her voice was fairly confident when she said: "It should be done at night. It should look like he expired in his sleep. No blood—too messy." Farah moved to sit on the floor in front of Geeta, who sat on her cot. "Well, how did you do it before? To Ramesh?" "None of your damn business." "Fine." Farah sighed. "So are you gonna come over to my place now or ?" Geeta narrowed her eyes. "I said I'd help you, I didn't say I'd do it for you." "But you're smarter than me. You'll do it right, I know you will. I'd just mess it up." Geeta scoffed. "If you used this much butter on your food, you wouldn't be so scrawny." "'Arre, yaar,' it's not like that. I'm just saying you've already killed one, another won't make a difference." "Your 'chut' husband, your murder." Farah again winced at Geeta's language but followed her and her lantern out into the night. They avoided the open water channels, walking along the sides of their village's common pathways, where garbage aggregated. Farah covered her nose and mouth with the free end of her sari. Her voice muffled and miserable, she asked, "What are we doing here?" Geeta doubled over, her head closer to the ground as she squinted. "Looking for a plastic bag." "Why?" Geeta modulated her voice as though it should've been obvious: "Tie his hands and feet while he's sleeping and then put the bag on his head. Smother him. He dies. You remove your nose ring; I keep my money. Everyone is happy." "Smart." It was almost sweet, the way Farah looked at her. Like Geeta's ideas were gold, like she could do no wrong. Despite herself, such adoration filled her with the desire to prove Farah's faith was well placed and to perform as best she could. Geeta imagined this was what having a child would've been like. "I know." "So, ah, is that how you did it?" Geeta stiffened. She rolled her shoulders back to make her height more imposing. "If you want my help, you'll stop chewing on my brains with your questions. What I did is none of your damn business." Farah looked chastised. She sucked her teeth, complaining, "'Bey yaar,' fine. What do I tell people? After, I mean?" "Heart attack, he drank himself to death, anything you like. Just don't let them do an autopsy." "Okay." Farah drew out the word slowly. "But if you smothered Ramesh, why didn't you just use a pillow? A plastic bag seems like a lot more work, you know?" Geeta blinked. Dammit. That thought had not occurred to her. She covered her ignorance with ire. "I didn't say I smothered Ramesh." Farah threw her hands up. "What? Then why are we here? Why not just do what we know works?" "Oi! 'Even to copy, you need some brains.' Do you want my help or not?" "What I want," Farah sulked, "is your 'experience,' not your 'experiment'." "Forget it. Why should I break my head over your drama?" "No! Sorry, okay?" She tugged on her earlobes in an earnest apology. "Let's keep looking, na?" They walked along the more trafficked areas, where the lines of compost and trash thickened. Geeta toed aside torn packets of 'mukhwa's and wafers. A few meters away were the public toilets the government had recently installed. There were two, designated by helpful yellow and blue cartoons of a card deck's king and queen. Though she used the squat toilets daily, it'd never occurred to Geeta before now just how silly the drawings were. Geeta's home didn't have a pit latrine like many others did, but she still saw men take to the fields. Despite all the recent clamoring about open defecation and sanitation issues, it didn't bother her; she'd grown up doing the same, they all had. Even those who had pit latrines declined to use them—after all, someone would eventually have to empty them and caste Hindus were quite touchy about polluting themselves by handling their own waste. Some tried to force such work onto local Dalits, an oppression that was technically illegal, though authorities rarely came around these parts to enforce the law. But for women, the new installations, public and private alike, were wholly welcome. While men could take to the fields at their whim (Geeta had heard that in the West where there were clean facilities galore, men still 'su-su''d anywhere for the hell of it—nature of the beast and all), the women and girls could only make their deposits either at sunrise or sunset— otherwise they were inviting harassment. So they held it. Better to brave the scorpion than the horny farmer. Around Geeta and Farah, the crickets' song swelled. It was difficult to hear Farah as she ambled along another line of rubbish, her attempts half-hearted. After picking up and immediately dropping a bag of chips with carpenter ants inside, she asked, her voice carefully casual, "How come Ramesh's body was never found?" Love this book? Buy a copy online.

| |||

| Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri | |||